Key Points

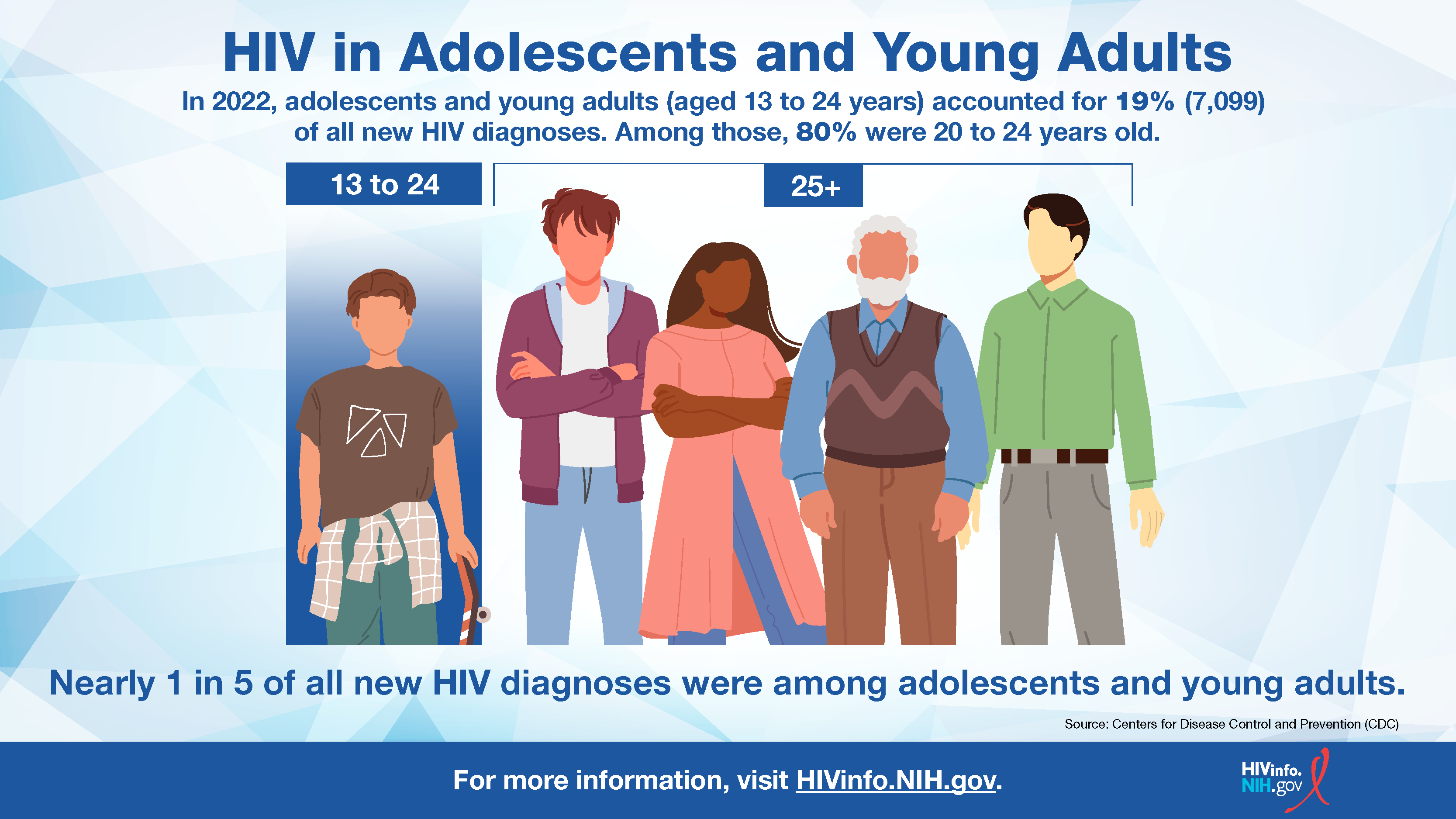

- Adolescents and young adults (AYA) account for 19 percent of new HIV diagnoses in the United States.

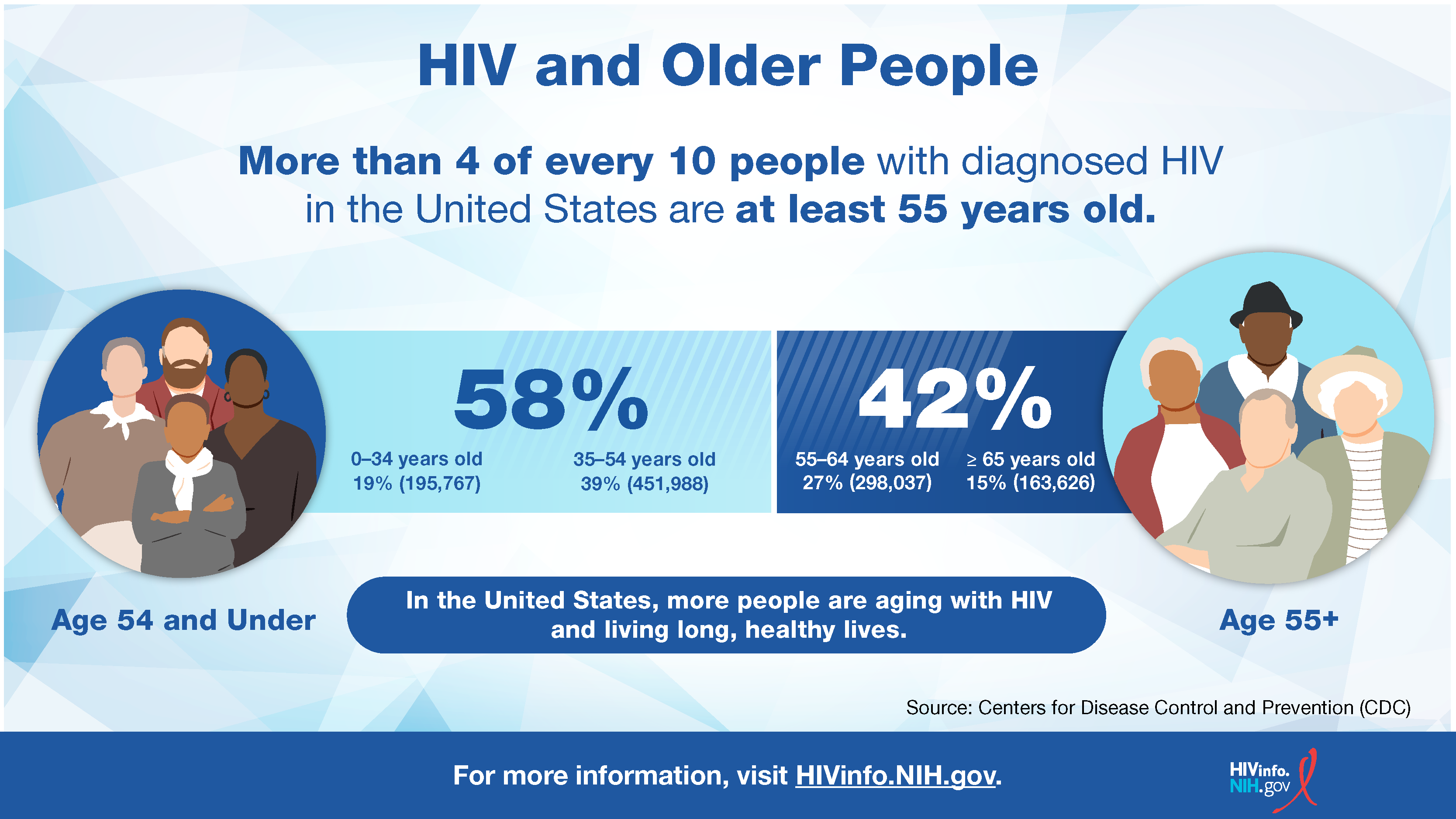

- With treatment, AYA can live long, healthy lives with lifespans comparable to those of people without HIV. HIV medicines can also effectively eliminate any risk of sexual HIV transmission to others.

- Most youth who acquire HIV during adolescence do so through sexual transmission.

- AYA may face challenges adhering to an HIV treatment regimen due to concerns about HIV-related stigma.

Does HIV affect adolescents and young adults?

Yes. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), adolescents (13 to 19 years of age) and young adults (20 to 24 years of age) made up 28,087 (3%) of all people living with HIV in the United States.

In addition, adolescents and young adults accounted for 7,099 (19%) of the 37,981 new HIV diagnoses in the United States and dependent areas in 2022. This means that about one in every five new HIV diagnoses was someone between 13 and 24 years old.

![HIV in Adolescents and Young Adults]()

How do AYA get HIV?

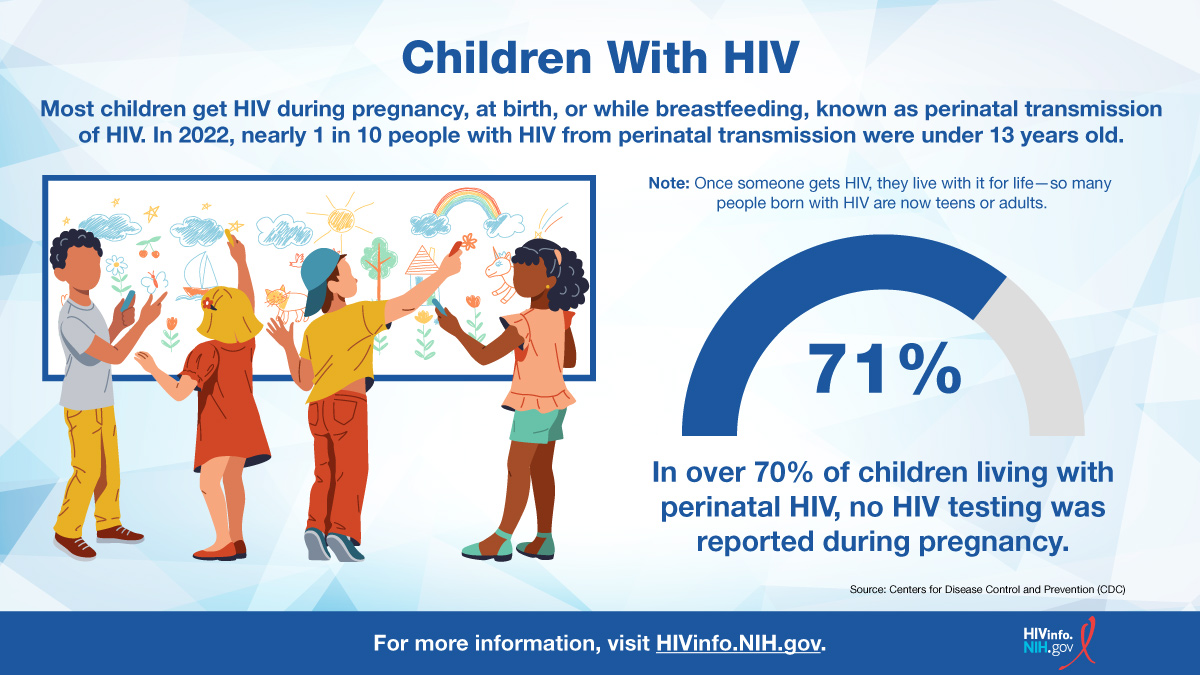

Some AYA with HIV in the United States previously acquired the virus as infants through perinatal transmission. However, most adolescents and young adults with HIV acquired it through sexual transmission.

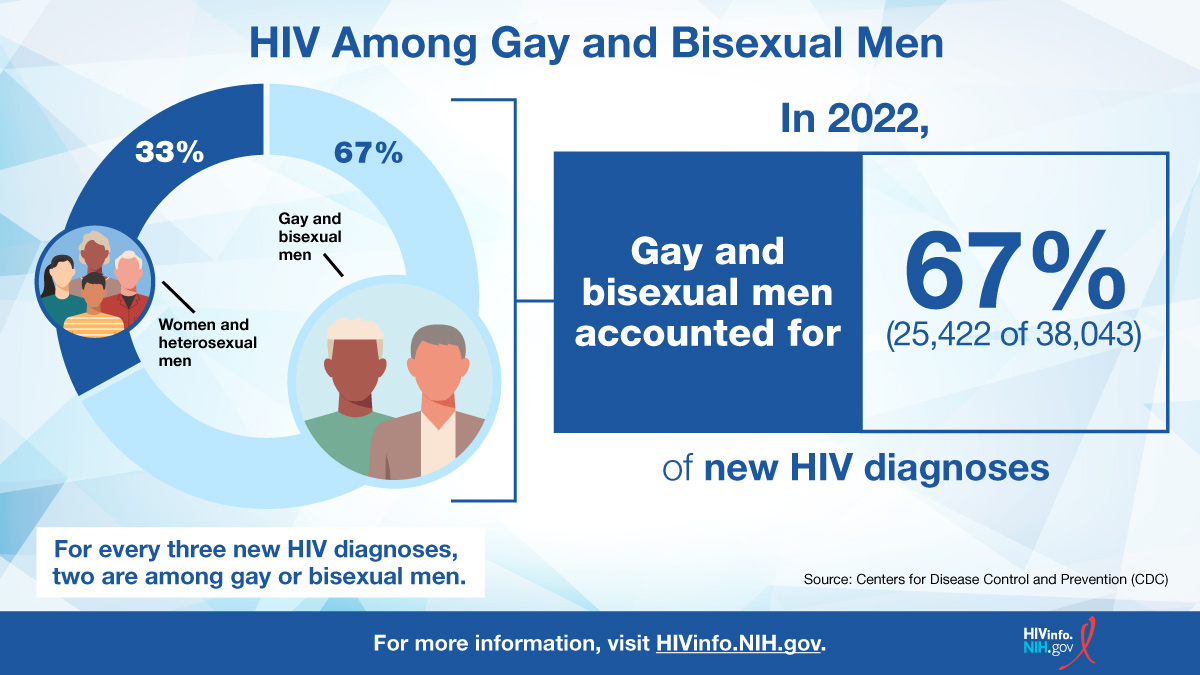

Most male adolescents and young adults diagnosed with HIV acquired HIV through male-to-male sexual contact, whereas most female AYA diagnosed with HIV acquired it through heterosexual contact.

What factors increase the risk of HIV in AYA?

Several factors increase the likelihood that AYA may acquire HIV:

- A lack of basic knowledge about HIV. A greater understanding of HIV prevention, testing, and treatment can help reduce the likelihood of HIV transmission.

- Low rates of condom use. Always using a condom correctly during sex reduces the chances of getting HIV and some other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

- High rates of STIs among youth. An STI increases the risk of getting or spreading HIV.

- Alcohol or drug use. AYA under the influence of alcohol or drugs may engage in less safe sexual behaviors, such as having sex without a condom.

- Injection drug use. HIV can be transmitted through blood when sharing needles or drug “works.”

About 44 percent of AYA with HIV do not know they have it, and about 34 percent of AYA diagnosed with HIV are not virally suppressed. Together, these factors create unique challenges for preventing HIV transmission among AYA.

How can PrEP benefit AYA?

Adolescents who are at risk for acquiring HIV can benefit from pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The word “prophylaxis” means to prevent or control the spread of an infection or disease. PrEP is used by people without HIV who are at high risk of being exposed to HIV through sex or injection drug use. PrEP medicines are not for people who already have HIV.

In 2018, the FDA first approved an HIV PrEP medicine to include adolescents weighing at least 77 lb (35 kg) who are at risk of acquiring HIV. Although PrEP use increased from 8 percent in 2017 to 20 percent in 2021 among all applicable AYA, increasing use could help to further reduce the risk of HIV transmission in this group. Notably, Black and Hispanic individuals were less likely than White individuals to use PrEP.

Three HIV medicines are currently FDA-approved for HIV PrEP. To learn more, read the HIVinfo fact sheet Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis.

Can adolescents get PrEP medications?

PrEP medications can be prescribed by a pediatrician and are also available through many local health departments and community health clinics. PrEP medications are usually covered by most insurance companies, but uninsured individuals can find free or affordable PrEP through the CDC’s Paying for PrEP webpage.

Legal issues about consent for clinical care, status as a legal minor, and confidentiality are important considerations for providing PrEP medications to adolescents under 18 years old. The legal rules and regulations vary considerably by state.

For detailed information about the use of PrEP in adolescents, see the CDC’s Preexposure Prophylaxis for Prevention of HIV Acquisition Among Adolescents: Clinical Considerations, 2020.

What factors affect HIV treatment in AYA?

Treatment with HIV medicines (called antiretroviral therapy or ART) is recommended for everyone with HIV, including AYA. HIV medicines help people with HIV live long, healthy lives and reduce the risk of HIV transmission.

Several factors, including growth and development, affect HIV treatment among AYA. For example, because adolescents grow at different rates, dosing of an HIV medicine may depend on their weight rather than their age.

Issues that make it difficult to take HIV medicines regularly and exactly as prescribed (called medication adherence) can affect HIV treatment in adolescents. Effective HIV treatment depends on good medication adherence.

Why can medication adherence be difficult for AYA?

Several factors can make medication adherence difficult for AYA with HIV. Negative beliefs and attitudes about HIV (called stigma) can make adherence especially difficult for AYA with HIV. To avoid stigma or judgment from peers, they may skip medicine doses to hide their HIV status.

The following factors can also affect medication adherence:

- A busy schedule that makes it hard to take HIV medicines on time every day

- Side effects from HIV medicines

- Issues within a family, such as physical or mental illness, an unstable housing situation, or alcohol or drug abuse

- Lack of health insurance to cover the cost of HIV medicines

- Relying on a parent or caregiver to get HIV medicine and attend appointments

The HIVinfo fact sheets HIV Treatment Adherence and Following an HIV Treatment Regimen: Steps to Take Before and After Starting HIV Medicines include tips on adherence. Some of these tips may be useful to AYA with HIV and their parents or caregivers.

This fact sheet is based on information from the following sources:

From CDC:

From the HIV Clinical Practice Guidelines at Clinicalinfo.HIV.gov:

- Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents With HIV:

- Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection:

- Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States:

Also see the HIV Source collection of HIV links and resources.